Dr. Christine AmiNCAP Grant Manager and 2020/21 American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Mentor March 31, 2021: I couldn't image a better last day of National Women's History Month than with a book discussion on I am Malala followed by a memoir writing workshop with none other than the president of the American Indian College Fund, Cheryl Crazy Bull!

Throughout our Virtual Connection, we had the opportunity to hear from several of the other Indigenous Visionaries fellows from: Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College and Salish Kootenai College. We touched upon some key points and personal connections with the text. I was particularly impacted by commentary from our own NCAP Visionary, Tammy Martin, who pointed out that she read the story of Malala, a young girl who was shot by the Taliban for advocating for eduction, through the eyes of young Nobel Peace Prize winner's parents. Our discussion moved from takes on feminism to the power of writing for women. One of our College Fund facilitators brought forth a quote from the reading that highlights the act of writing as activism. Malala writes:

I know, I know - I am getting a bit jargony here - but hang with me for a sec or two... Specifically, Spivak highlights: "Can the subalern speak? What must the elite do to watch out for the continuing construction of the subaltern? The question of 'woman' seems most problematics in this context" (90). Through her critical eye of Foucault and Deleuze, she concludes: "The subaltern cannot speak. There is no virtue in global laundry lists with 'woman' as a pious item. Representation has not withered away. The female intellectual as intellectual has a circumscribed task which she must not disown with a flourish" (104). So the question remains - how does the intellectual, even the female intellectual, represent these voices without being condescending, without commoditizing their knowledges and their experiences, without engaging with epistemic violence of academia? For Malala the answer is clear, don't wait for the academic - write for ourselves. Just as my mind started to wonder further into memories of literary theory and gender studies lectures, inquiries of what/who defines an "intellectual", and the complexities of my role as a Navajo woman with a Ph.D. in academia, our Indigenous Visionaries event flowed into a memoir writing workshop - I see what you did there, College Fund people... read a memoir, workshop our own memoirs ;)

You see, I write in stories - a highly controversial form of data delivery in the academic realm - second reader responses typically echo: where is the hypothesis?; is this the introduction?; why can't you just get to the point?; is this creative writing?, is it theory?, is this even research? My introductions are usually snapshots of when the perplexities of the study have culminated in a personal setting and my conclusions are usually finalized with my traditional introduction, reaffirmations of who I am as a Navajo woman. In between are hypotheses, data, theory and research. More importantly, these stories from my experiences, from my studies - both formal and informal - are how I learned to learn and how I learned to teach. From weaving to butchering, from graduate papers to my dissertation, from to my response to the Navajo Nation's president for silencing me to my current application for a National Endowment of the Humanities Grant - stories are where you will find my voice, my successes, my failures, my family - it is where you will find me. So vulnerability pretty much wraps up a lot of my anxieties about publishing. Cheryl pushed those vulnerability buttons and had us practice some writing - "How does your story start?" What better time to test out the starting line to my article draft, entitled: "A Native Scholar Pushing Back: Epistemological Imperialism, Academic Gaslighting, and Credential Theft". What would people say? What would my peers think? Despite the fact that the group I was writing with could not have been more supportive, vulnerability creeped in. Oh well... here I go: In the stillness of my home before the sun rose, before my children, husband and animals awoke, I was trying to make sense of the theft of my Indigenous research credentials by a non-Native former colleague. Heads nodding - That's a good zoom sign. A voice reached out: "I would read that!" Another voice followed, "Yeah, I would too." Followed by another, "Now, I want to know what happened!" Validation of my experience, of my voice, of not only others hearing me - but of others listening to me. It was only the first sentence and the story was still to come, but it was an opening line that epitomized a crucial moment in my life as an academic and a Native woman and which also interwove my experience in complex sociopolitical realities of the Native American Studies discipline. After our workshop, I thought about what was shared and what it means for a Native American Woman to write down her stories. My fingers reached for one of the first Native women's anthology that I had ever read, Reinventing the Enemy's Language (1997). Julia Coates, Councilor for the Cherokee Nation's Legislative Branch, and my first Native Women's Literature professor at UC Davis, introduced me to this compilation of poems, songs, and essays that bring to life the "beautiful survival" of Native women, including all of the ugly as Joy Harjo declares: "We are still here, still telling stories, still singing whether it be in our native language or in the 'enemy' tongue" (31). As my mind returned to the issues brought forth by Spivak, these questions returned: How can I write about Navajo women, from my position as an academic, and encapsulate their voice with mine? And then I thought - why do I have to encapsulate ALL Navajo women and why do I have to write like a western academic? What I write about is my experience as a Navajo woman and I write in stories.

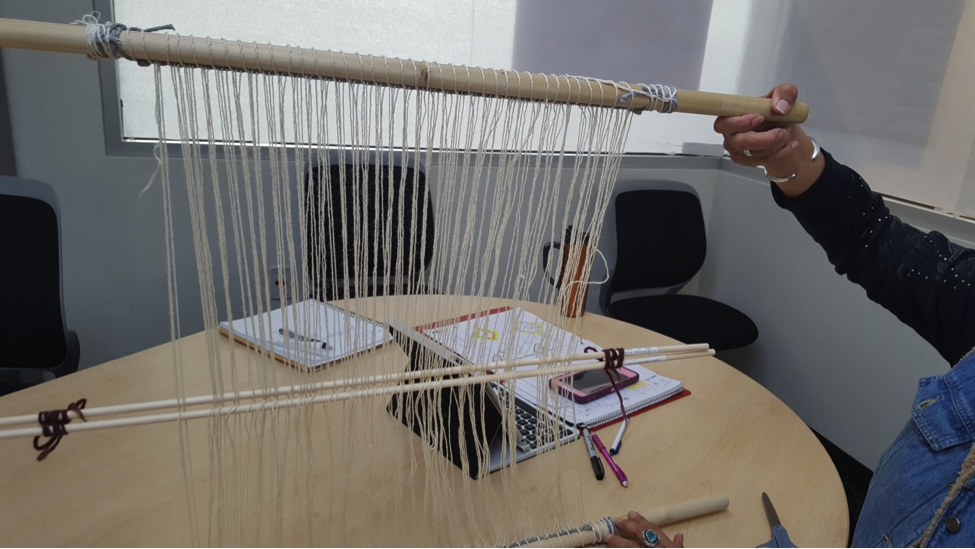

These sensory textile narratives constitute creative acts of writing, complicate constructions of Indigenous feminisms, and promote cultural sovereignty through means other than the enemy’s language. And as I thought of those words and my place in academia, I thought of my grandmother. I thought of how she told me stories - it was through weaving. Weaving is our memoir - In the warp are stories of her survival and mine. Each line is a recap of my day, smooth hooks retell my successes, each section unwoven is not only the presentation of one of my failures but also my reattempt at troubleshooting the problem at hand. Inside my weavings are my thoughts - my family - my research - my vulnerabilities. Inside my weavings are told, unseen stories. I haven't woven a complete piece in years - work and life have kept my loom covered. I tried to look at my weaving tools that were my nálí's who passed away from COVID complications in July. But I just wasn't ready. But today - today is different. Today I picked up my spindle. The warp, my hand, my thigh became one instrument. My spit used to mat and settle the warping mixed with the wood of the spindle and in return that taste of wood brought forth the memory of the feel of my nálí's velveteen skirt - coated with a slight tinge of mutton grease. The sound of my spindle on the floor joined the sound of her spindle in my memory. Just like that - My grandmother, Cheryl, Gayatri, Julia, Joy, Inés, and I, we started a new piece - In this warp is the outline for my next memoir - this one includes the stories of the Visionary fellows and how they got their mentor to weave once more. It is filled with the vulnerabilities we discussed in our workshop, power that is associated with learning to write ones story, and continuation of our ways of knowing with a weaving comb in hand.

0 Comments

Tammy MartinNavajo Weaving BFA Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Fellow

She was very happy with her sale because she got to keep the money. This money allowed her to buy graduation items she thought she wouldn’t be able to afford. She went on to attended Navajo Community College (now Diné College) and earned a certificate. She uprooted from her home area and moved to the Eastern Agency community of Crownpoint. It was here that she worked at Indian Health Services, the Navajo Nation Police Department, the Office of Vital Statistics, and Crownpoint Community School. She had married, had a family and a place to call home. Weaving became therapy because she soon found herself a victim to domestic violence. Two years after filing for divorce, her oldest daughter became ill with leukemia and passed away in April. During these trying times weaving de-stressed her and provided an extra income. Five years later, she married Kenneth Begay, a big supporter of Gloria and his stepchildren.

When teaching her students, she tells them to research other well known weavers and their textiles such as Roy Kady, sisters Barbara and Lynda Teller, Gilbert Nez-Begay, and Kevin Aspaas; they all have their own story for weaving, their styles are what makes them recognizable, even from a glance. She says “the more you learn about other weavers, the more you know about yourself and you can create your own style”. Learn your language, even if you know just a few words, you identify yourself as a Diné person; to learn that being Diné is unique. “No one can take that identity from you”. That is something that a lot of our youth are dealing with, they may feel embarrassed to speak it because they might get shamed for speaking; it should be that way, we should be encouraging all the youth to speak our language. The last is something that she recalls her mother sternly telling her “You have ten fingers, those ten fingers are given to you so that you can take care of yourself; work with your hands”. This was not just a saying, it is the Diné philosophy of self determination or T’aa Awoli Bee. I recall my own grandmother saying that whatever you want or desire is at the very tip of your fingers, it's up to you to make the rest of the hand, mind and body to work to earn it. Sometimes, we take for granted how much work you put into something has its own rewards, or sense of accomplishment. We ended the interview encouraging one another to keep weaving, carding, spinning, and learning. In Gloria’s words “Weaving is a non-stop learning process”. Download the full recap of Tammy's interview with Gloria here:

Sue V. BegayNavajo Weaving BFA Student, CA315 Wool Processing II

I prepared the black walnut skin with a pre-soaking. Pre-soaking is required because the black walnut is very hard. I had my black walnut soaking for one day and one night. I prepared the labels on the skein and wet the weft. For this project, I used heather gray and blanche white from Brown Sheep Company along side some of my hand spun wool. After my skeins and weft were labelled, I dipped them in the prepared boiling pots of water. The water I used is from the unconfined aquifer water from Narrow Canyon. All the dyeing is done with unconfined aquifer water. I repeated the same process for the yellow skin onions- although I did not have to pre-soak. For each dye, I made two groups: one set made with alum and another set without alum.

My experience with dyeing with yellow onion skin and black walnut was very exciting. The colors of the weft are gorgeous with both yellow onion skin and black walnut. I learned about the slight various of natural plants as well as the differences using machine spun vs hand spun wool. Ultimately, what my major take away this week is that the beauty and gorgeous colors that comes from Mother Earth are treasures. Watching how the color comes alive.  UGG - My fault - Sorry, wool! UGG - My fault - Sorry, wool! Here are some other practical take aways I learned this past week: Lesson Learned: The wool is still very hot even after two baths. Lesson Learned: Never mix a pre-dyed skein with your skein you wish to color. Lesson Learned: Be patient and let the colors work. BIG Lesson Learned: This is what not to do. I put in a white skein and put a sky-blue skein on top of it and the color transferred onto the white skein. I can still use this in my pictorial rug as a corn tassel or streaks in the skyline. One of a kind weft. I am very honored to be in this class even though we are distance learning. It was absolute great day of hands on activities and I am looking forward to another great lesson. But for now...I saved some of my black walnut and I'll be testing it out with some Navajo churro raw wool. Tamerra MartinNavajo Weaving BFA Student: CA315 Wool Processing II

In preparation of dying wool, I found it interesting that it was encouraged to recycle or repurpose materials. There’s really no need to go and purchase everything new. You just have to look around and see what you could use. A metal basket with bailing wire could be turned into a strainer or empty water/milk jugs could be used to make tags to label your skeins.

Once the tea was ready; we added the unbleached white wool and the heather gray wool...the colors that came from the first dye bath were very subdued. The second dye bath, when the alum mordant was added, the colors was very bright! The first dye lesson was a success! When seeing the colors that developed from this lesson, I couldn’t help but think about the many other plants on the land that serve a purpose. Whether it was a natural remedy for an ailment, or an essential item for a ceremonial reason or a utilitarian item; these plants served a purpose. I am very honored to be learning these ways and that I can share this with my helpers. We are already looking forward to the next plant dye session.

If you are interested in joining the Navajo Weaving BFA program in the fall, be sure to get in contact with Christine Ami (cmami@dinecollege.edu) or Crystal Littleben (cclittleben@dinecollege.edu). It's a one of a kind program - only offered here at Diné College! Christine M. Ami, Ph.D.Grant Manager, Navajo Cultural Arts Program

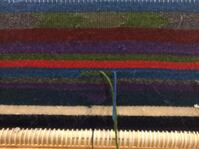

I would watch her weave for hours, sometimes laying on the floor with my eyes closed listening the thump of the comb as she carefully secured one line of wool to the next. I could follow the sound of the warp as she moved the batten in preparation for her next line. I would sit next to her while she wove and every once in a while, she would call me over to put a few lines in, watching how I handled the comb, worked with the weft, and practiced my turns. To sit in front of her loom for a photo op was strange - and while everyone in the room was laughing, smiling, and enjoying the last few minutes we had together before we headed off to Flagstaff, I knew at 10 years old that I wasn’t the weaver of that beautiful storm pattern rug despite what that soon to be developed film would present. This is a scene of what Philip Deloria could define as Playing Indian (1999) or what I would be inclined to call playing Navajo (check out my dissertation [Today, We Butcher: A study on Navajo Traditional Sheep Butchering, 2016] - it’s mostly on sheep and butchering but you can check out some insight to playing Navajo debates). It isn’t as uncommon as we would think and with today's technology - it happens almost spontaneously. Photo ops for graduations, weddings, tourism, magazines, Instagram and Facebook have sprung up in recent years with Navajo individuals pretending to be deeply entrenched with traditional practices, even assuming traditional artisan roles such as weavers, potters, basket makers, silversmiths, etc. I am not referring to photographs of Navajo individuals who document key moments of their lives where they have left their comfort zone to engage and create with their own hands for the first or billionth time. I am referencing those who knowingly have no experience with the art pretending to work on a cultural arts piece for a mere photo op, stealing intellectual property and artistic abilities. Most recently I was called in to assess an incident where an Instagram photo and Facebook video had been released of a Navajo individual who was pretending to be the weaver of a Navajo sashbelt in progress. I later found out that there was a Navajo run production team taking footage. They wanted some b-roll of Navajos weaving - what could be more of testimonial that our cultural practices persist in the heart of the Navajo Nation than an image of a beautiful Navajo woman sitting in front of a loom weaving? The only problem - there were no Navajo women weaving at that moment. But there were warped looms in a locked room with no one present at the moment to claim ownership and there was an available Navajo person willing to pose although had no knowledge of that style of weaving and were well aware that the weaving on the loom was not of their making. The loom was positioned incorrectly and hands that were not the artist moved the dowel that separated the male and female warp. Photos were taken; video was captured; posting on social media took place. In just a few moments – a theft had occurred. Stolen - credit of artwork. Stolen - intellectual property. Stolen - credit of the maker. Stolen - the intimacy between the sashbelt maker and their loom.

While there is a tremendous lesson to learn from this incident for those parties involved - they never offered to make amends with the weavers; they never offered their apologies to the looms. I was the one left to clean up the aftermath that they had created - I was the one who had to let the weavers know what I had found out about the violation of their creative space and the violation to their identities as Navajo weavers. A few days later on a cold Saturday morning we sat as a group and we talked while they wove - the looms listened. That day the weavers finished their pieces and began new sashes - the looms forgave them - the looms forgave me. Thinking about the event and the many other instances that I have seen on social media, television, and magazines where Navajo play Indian, I felt that there was a need for public discussion to take place about why it is wrong for individuals to pose for photos, pretending to be an artist of an art piece that they did not create, Navajo or not. So here are my ponderings ... each one worthy of their own posting or book.  Jonah Yazzie, Instructor, NCA206: Sashbelt Weaving Jonah Yazzie, Instructor, NCA206: Sashbelt Weaving Would an individual (Navajo or not) pose for a photo in front of a painting, sculpture or other fine art with such confidence as to suggest that that artwork in the photo was of their own making? Probably not. I've been asking my colleagues (who are weavers, painters, silversmiths, and photographers) this question - and their responses are overwhelmingly the same - absolutely not. Then my question remains, why would this be okay for someone to do so with a cultural art? The debate between the cultural and fine arts has been in existence for more than a century (Check out this oldie but goodie by Boas Primitive Art [1927]). This is the very rationale for creating a Navajo Weaving and Navajo Silversmithing BFA program. Graduates of this program are set to re-envision the future of the southwest Indian art’s culture and economic markets through visual sovereignty strategies. Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie’s (Seminole/Diné) posits visual sovereignty in “Dragonfly’s Home” in Visual Currencies: Reflections on Native Photography (2009) as “a particular type of consciousness rooted in confidence which is exhibited as a strength in cultural and visual presence” (p. 10). She continues, “visual sovereignty does not ask permission to exist, but … require[s] responsibility to continue” (p. 11). In this manner the NCA BFA Emphases seed its students with responsibilities to Diné community, culture, and ways of understanding the world through the language of art. What this sashbelt incident has taught me is that our BFA graduates have a lot of work ahead of them - working to confront the lack of cultural and visual respect that our cultural arts face from both within and without the culture. Their positions, their voices, and their work are stories of survivance. Does the fact that this was a Navajo loom, that it was a Navajo individual willing to pose, and that the production company was Navajo run make this theft okay? As Navajo people, we so easily charge non-Navajos with cultural misrepresentation, cultural appropriation, and even unauthentic authorship. With photography and videography in mind, we can look at the work of Edward Curtis, who for decades has been rightfully criticized by Native artists, activists, and scholars for his staging of Indigenous peoples for photos, blending two or more completely distinct indigenous populations for the purpose of capturing the "Indian" before he vanished. Curtis' most exemplifying piece of our Navajo culture fading off into the sunset is found in his composition of Vanishing Race. The location of our dismal future was contained within the walls of Canyon de Chelly, whose canyon mouth is less than 30 minutes from Tsaile. Images of colonization and the theft of our indigenous visual sovereignty was and is not a hard sell for these Edward Curtis case scenarios. So.... ...what happens when the lack of cultural and artistic respect is committed by our own people? As I was searching for answers, trying to understand why this incident had taken place, I replayed to the rationalizations presented to me by those who were involved in this incident: “I didn’t know it was a classroom,” “There are looms all over campus,” “We just used the loom as a prop,” “We weren’t playing,” “I’m a weaver - I know it is not okay to mess with someone’s loom," "If I knew it was someone’s, I would have never,” “I’m never going volunteer for anything again,” “We didn’t have time to find a weaver,” “I’m sorry. I should have known better”. I could continue but you get the idea - the excuses are endless. For whatever the intention, rationalization or excuse, scenarios such as these are not only demonstrations of a lack of respect for our own cultural arts but also for our own people. This is internal colonization at its best. No longer is it an outsider who wishes to capture our people in the thrust of cultural exoticism; rather, it is our own people who have staged these scenes to maintain the static visual representation of what a Navajo should look like and should know how to do. We self imposed what people like Edward Curtis had visually depicted of us. We self-romanticize, self-fetishize - and in the end - for what purpose? - To continue to prove to the outside world that we are still Navajo? Or worse, to prove to ourselves that we are still Navajo? Or worse yet, we just want a pretty picture for Instagram? In any of these scenarios the larger issue is about respect, or rather, lack thereof. Lack of respect for the artist, the loom, and the weaving. It also suggest a lack of self-accountability of the individuals who see no harm in just taking a picture. And after reflecting upon this scenario, the excuses presented to me, and understanding the internal colonization at work - I don't think that those individuals who were involved in those photos understand the complexities nor the ramifications of their actions; moreover, since, I was the one blocked from Instagram and Facebook profiles, it appears as if they feel as if it were their personal space that was violated - not the weavers who were creating on the looms. Their social media block serves as a hope that I could never reprimand them for their posting of culturally appropriating photos again. It was a failed attempt to make me feel as if I had been the one who overstepped my boundaries. Regardless of the displaced anger of those who sat in front of the loom that wasn't theirs, one of their excuses continued to linger on my mind: "the looms were just props." How could these looms be used as mere props when their existence alone represents the world around us, the deities who we pray to, and the elements of nature who challenge us? Weaving looms are not coat hangers; they are not pull up bars; they are not jungle gyms for children; they are not props. These looms are our world (Check out the Bee ádeil’íní: Navajo Cultural Arts Language Series segment on the cultural teaching of the loom for more insight on the cultural teachings of the loom). And while to many, one sashbelt is the same as the rest, serving as a perfect Navajo background to authenticate Navajo photographic status, to the sashbelt weaver there are so many distinctions between each creation. From geometric and algebraic calculations, wool, yarn, or cotton selections, respinning decisions, to the accompanying songs, prayers and thoughts woven into each piece that will journey with the person wearing the sash during their intended occasions - each sash is unique and each sashbelt weaver is keenly aware of that. There are reasons why and when an individual can or cannot wear or use a sashbelt, many of which are associated to key transitions in our life like puberty, child birth, and after giving birth. Moreover, in none of our cultural teachings does the rationale "I need it for a photo" justify the use of a sashbelt or the need to sit in front of a loom and pretend to be the weaver. With that, this scenario and those similar bring up a larger and perhaps more frightening question: does the aesthetic perpetuation of cultural arts trump the perpetuation of the cultural art skills, knowledge, and purpose? The creation of the NCAP was to (1) continue the intergenerational transfer of Navajo cultural arts knowledge; (2) perpetuate the technique and skills of the Navajo cultural arts, and (3) reconnect the cultural teachings to the cultural arts practices. While aesthetics matter for a plethora of reasons, including rather practical issues such as fit, wear, and use, the empowerment of our cultural arts teachings, skills, and purpose should and must trump the mere "playing Navajo" mantra. We are Navajo people, not because we wear Navajo cultural arts but because our mother's have given us that birthright and with that birthright comes responsibilities to our way of life. Being Navajo is more than playing a Navajo model, more than having a census number, and more than "coming home" to vote during elections. Being Navajo entails community and cultural obligations that tie us to our land - including an engagement with, respect for, and responsibility to our cultural arts skills, knowledge, and purposes. At the NCAP we have witnessed the transition of young Navajo artists from mere inquiring minds to culturally and technically fluent cultural artists. We have experienced, as staff, the possibilities that this knowledge holds for both the students and the teachers. That proof, for us, is more than enough cause to continue our outreach programs - exposing the cultural teachings that come from the loom as more than pretty picture material - but rather, as a way of life that is at times harsh but rewarding in more ways than we can empirically record. Ultimately, why would there be allowances for presenting false visual stories to the world when we have specialized artists and people who dedicate their studies and their lives to these arts who could be spot lighted - showing the world real stories of survival, resistance, and survivance? There is no need to “play Navajo” for the purpose of an image. We do not have to fit the Edward Curtis mold of what a Navajo individual should be posed as. As Navajo people, our visual stories are so diverse. However, for those who maintain, perpetuate, and celebrate our cultural arts, while they connect to our greater history and future of who we are as Navajo people - please let their stories be their stories. Our looms, our weavings, and our cultural artists have voices, lives, and agency. Let’s not take that away from them for the sake of “likes” or ❤️'s to be hoarded on social media networks. If we are looking to capture an image of a weaver – let the person in the photo be a weaver. Let the work in the background reflect their work. Let’s take the time to talk with, learn with, and highlight our cultural artists - showcase their work, promote their small businesses, and celebrate them. Yes, we must build rapport and establish relationships with our cultural artists. Yes, we need to help to protect our cultural artists by becoming more self-aware. Yes, this will take time. In the end, the time it will take to create this connection is in no way comparable to the quantity and quality of time, effort, and sacrifice that these artists have put into learning their work. We want to do more than just listen to their stories - we want to hear them. Through visual sovereignty, we as Navajo people, can help people hear those stories by way of images - so let's stop playing Navajo.  Weaving on my loom with my nálí's weaving on the wall, ever vigilant, ever protecting Weaving on my loom with my nálí's weaving on the wall, ever vigilant, ever protecting With that, I return to that day when my dad was taking my photo in front of my Nali’s loom. It is both similar and distinct from the sashbelt loom incident. Similar in that photos taken from these scenes would reveal false stories of who the weaver was/is. Distinct because at the end of my dad's photo session, my grandmother sat next to me. I remember that she took my hand with the comb still in it and guided it with sound. In that moment - it was as if she opened a window for me, teaching me how to find my own identity and my own healing (check out our Cultural Arts Holistic Well-Being Series). As I grew up, with some luck, some family support, some amazing teachings from weavers like Ilene Naegle, Roy Kady, Jeannie Jones, Jonah Yazzie, and TahNibaa Naataanii and a lot of honest time in front of my own looms, I found out what a loom can do for me holistically. My loom, that I must admit needs a bit of dusting off as of recent, saved me in many ways. Weaving inspired me to start speaking the Navajo language and helped me to deal with depression, insomnia and years away from the reservation. And although I have accrued just a shadow of my nálí’s skills in weaving, she still inspires me everyday that I pass her weaving that is hung in the center of our home. I would never want anyone to sit in front of her loom again and claim credit for her inspiration.

Tamerra MartinNCAC Emerging Artisan 2018/19 (Weaver)

Personally, I took it as a true test to see how confident I was in setting up a loom. The very first part of the process was to start with the warping. What would be an adequate size for a community loom? Enough that it could get finished within a week? I was taking into consideration to many things….on the day of setting up the loom, I packed what I thought we needed. Surprise! Of course, the zip ties I brought weren’t long enough, so now to look for wire. The words of our weaving instructor came to mind, “Make sure you have everything on hand, you don’t want to say ‘I don’t have it’ and put off weaving”. Should have packed the wire! Eventually, it was set up and ready to be created. I sat to the loom first; we were taught that the first couple of wefts are the foundation of your creation. You think positive thoughts about the weaving, the process it takes to complete and the journey upon completion. My thoughts were that whomever took the time to add a few or even more wefts would find themselves in complete peace and contentment. There is so much going on in the world and in our own lives today that sometime we forget to think about the present, “the here and now”. If you have had the chance to sit down to the community loom to weave or even just to admire it, I hope that you had a moment of tranquility. I encourage you to make a visit to the museum exhibit, have a seat and add a few lines. You will not walk away disappointed.

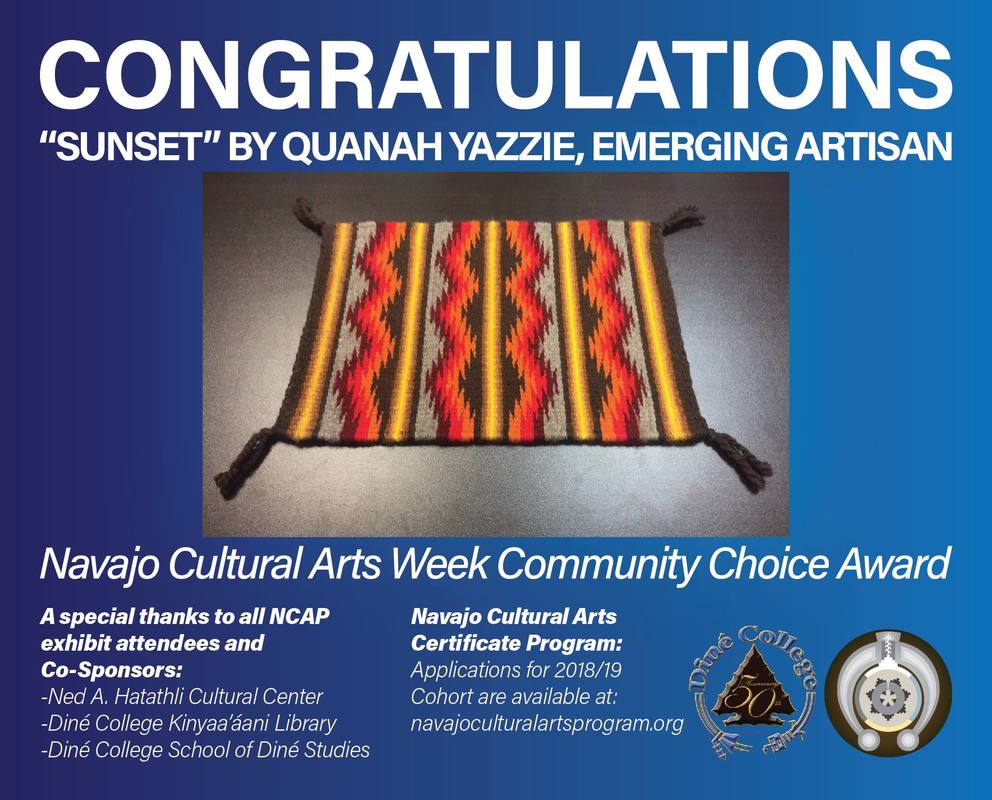

Quanah Yazzie Emerging Artisan, 2017-18 Cohort (Silversmith/Weaver)

As a young Navajo person, I have made it my life’s goal to keep tradition, culture, language and history of my people strong and resilient from complete globalization and influences that affect the Navajo tribe from cultural extinction. The Navajo Cultural Arts Program (NCAP) has been one of the first steps into giving me hope and inspiration to providing knowledge to our people in the future. As a student emphasizing in Weaving, I had the chance to emerge and strive towards a mastery level. NCAP has been one of the most exciting and best decisions I have ever made in my life. While growing up, I lived with my grandparents after the death of my mother when I was 6 years old. I remember how much I’ve grown to this day culturally. I first learned to weave by only observing and talking with my grandmother. I never actually attempted to warp a loom in my lifetime until this past year during a workshop I’ve attended in Phoenix at the Heard Museum. I was shockingly surprised by myself when I wove my first rug that came out beautifully. My first piece - done at the Heard Museum I found myself weaving like I knew how to do it already. My movements were natural and flowed smoothly as I reached the top of the loom to finish the rug. I think it’s amazing how my mind and my body kept a little part of something that I didn’t inherit completely. It was from this day on, I felt that I could do so much more. One thing, you should know is that I am a graphic designer. I come from a mother that painted, beaded, made moccasins and learned a lot in fashion. She was great. My father was also a painter and beader. So, I was not surprised when I started to drift towards more of becoming an artist myself. I learned a lot of my techniques while going to school at Arizona State University and Mesa Community College in the Valley. I came home after 6 years to live with my family and reconnect myself to our Navajo ways. I found a perfect way to merge my two lives into one when I joined NCAP. I learned so much from master weavers and my instructors at Dine College. I find myself visualizing more designs and recently started to experience a lot with color. A lot of what I do now is more contemporary, where color is more heavier over traditional design. I have a very long way to go to perfect my technique in weaving. My motivation increased recently when I was awarded the Community Choice Award in the NCAP Museum Exhibit in April 2018 for “Sunset”, a traditional wide ruins rug infused with fiery colors. This has been a wonderful experience with NCAP. I currently have a larger loom up and going that looks stunning in its earlier stage. As an emerging weaver, I encourage the younger generations to learn more about our cultural arts. Weaving is a medicine. When you weave, your body heals itself mentally, spiritually, physically, and emotionally in ways you can’t imagine. I found something for myself that utilizes my life’s teachings and knowledge to find a place in this world. It’s never too late to find yours.

Ahxéhee’. Thank You. Johnnie Bia, Jr. Diné College Psychology BA Intern, Office of Miss Navajo Nation

Sharonna is Coyote Pass clan, born for the Mexican People clan, her maternal grandmother is Bitter Water clan, and paternal grandmother is of the Red Bottom People clan. She is originally from Lukachukai, AZ. She is 24 years young. She recently received a Business Administration BA from Diné College. She is the Office Manager the Diné College Office of Institutional Planning and Research. Both of Sharonna's grandmothers weave and she feels extremely fortunate to be the only grandchild who can weave on both sides her family. Her paternal grandmother weaves the Yeii bi Cheii’s designs and had to have a ceremony that would give her permission to weave this sacred pattern. As for her maternal grandmother, she weaves two-faced rugs. Those rugs have one image on the font and another image on the back.

I asked Sharonna about some of the physical activities outside of weaving that directly enhances her cultural arts work. She shared that sleep, good posture, and home tidiness are most important. Sitting to long makes a person slouch when their progressing upward with my rug and it ruins a person’s posture so it would be nice to have some chair or cushion that will help them on their posture. Economically, Sharonna does not sell her rugs but there are many individuals who do sell their creations. When other artists sell their rugs, the money is used to purchase more tools or to help the person get by with life. Within the Navajo Nation there are those who make weaving as a career because it is the only income that they receive. The NCAP cohort watched a documentary called "Weaving Worlds" to explore the complexities of Western and Traditional concepts and practices of selling rugs.

Sharonna also talked about how making cultural arts products contributes to her mental stimulation. She envisions the rug before it takes shape and that planning helps to guide her wool. But that doesn't mean that the rug will turn out like her original plan. Many of her creations would just come to her or they would be changing and making their own image until completion. So she learned to be flexible and listen to the design. Two positive things that can enhance both mental and cultural arts well-being are 1) knowing how to manage your time and 2) getting information and strategies about weaving before your start. So deadlines and strategic planning are necessary especially as she does plan on making her own dresses and blankets designs in the future. In the meantime, she has plans to improving her one sided rugs and exploring ways on how to get two different pictorial images on a double sided rug. These tests keep her mind constantly moving, anticipating problems, and strategizing how to overcome those problems.

solid colors but there is always that one color that she picks to stand out more than others, and her designs are steps with images which tells a story of her life when she would start from bottom. She takes time for prayer, fasting, meditation, and enjoyment of her creation processes. There are certain songs that are used for weaving when starting and as you are weaving. For Sharonna, she only know two songs. When she sings and weaves, her rug grows faster and it is straight with no mistakes. Upon completion she thanks the creator and her grandparents on what they taught her, and also for helping her on getting the rug done and not having her lose herself in the process. She knows some stories about rug weaving, to her understanding there are so many stories that apply to the rug and its process from making the wool and taking the rug down. The positive activities she does to nurture her spiritual life and cultural arts practices are following what she believes in without thinking about it failing, or without having anything get in the way of her ethical values. In conclusion, weaving has been in our history through Traditional prayers, songs, and stories. It goes along with our way of life through the sheep we have, how we take care of our sheep, and how we use the wool off the sheep. It teaches us how to make our Navajo people be creative in their own way, incorporating spiritual aspects. Our hope is that Navajo Rug Weaving will continue to flourish among our Navajo people as we continue to move forward in today’s generation. If you have time April 13-20, stop by the NHC Museum at Diné College to check out the variety of weavings created by our NCAP Emerging Artisans for our 2018 Navajo Cultural Arts Exhibit. We will have 25 pieces of textile, silverwork, basketry, and leatherwork on display - all vying for best of show. Don't forget to vote for your favorite exhibit entry - winner will be selected as the "Community Choice Award"!!!!

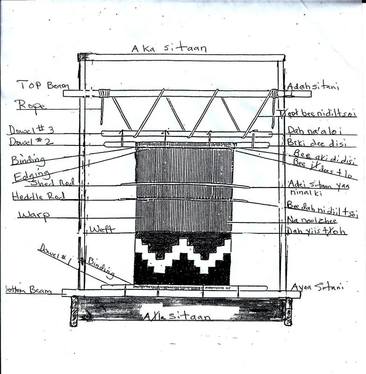

Sue V. Begay 2017/18 Apprentice Hi blog readers! Do you remember me?! My name is Sue V. Begay an Emerging Navajo Artist from Dennehotso, AZ-Navajo Nation-USA. I am a proud member of the Navajo Nation. My clans are the Hashtl’ishnii clan born for the Kinyaa’aanii, my grandfathers are the Tabaaha and paternal grandfathers are the Kinlichii’nii. You may remember me from the 2017/18 Navajo Cultural Arts Certificate Cohort – I was learning the cultural art of Moccasin Making and enhancing my skills in Weaving. Last year, my moccasins “White Shell Woman” took home the Board of Regents’ Choice Award at the 2017 Navajo Cultural Arts Exhibit. I am now in the NCAP Apprenticeship Program and under the guidance of Master Weaver TahNibaa Naataanii. The Apprenticeship Program is for NCAC graduates like myself who want to continue their learning in a more specialized fashion. During the application process, we submit interest to work one-on-one with a mentor. This is my fifth week in the apprenticeship. I can honestly say that my learning about weaving has grown tremendously since day one when I met with TahNibaa and her mother Sara. That day we spent getting to know each other – our strengths (and my weaknesses). It’s a good thing I know when to ask questions – because I sure had a lot of them! My first lesson was on terminology. I didn’t know what some of the rug weaving terms were and I got a quick lesson that first day. The vocabulary words that I learned are the “S” and the “Z” twists, rolags, skein, fine weight, medium weight, and heavy weight.

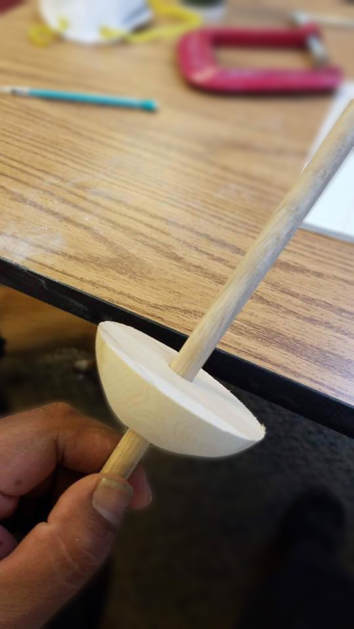

With TahNibaa’s assistance, I ordered my a Niddy Noddy, drop spindle, and carding tool for myself. If you are going to do things right – you need to have your own tools, she stresses. This way I can practice at home the proper way of handling my spindle. With the tools ready, I learned how to do the “Navajo three ply,” which is also called the “chain”. I learned how to do the “Andean wrap” on my hand. And with those first meetings under my belt, I was sent off with more homework – to use those techniques to make the edge cords of one of my rugs.

Things that I learned are going to help with my future rugs. Proper warping and how to “dress a rug” have been just a few of the techniques that I have learned. All this new knowledge, I just soak up the information like the wool soaks up the water. I can only get better and I plan to work hard at the skills that were introduced to me. NCAPERS (Alumni and Current), if you are (1) a NCAC graduate or will be by Summer 2018 and (2) are interested in the being an apprentice, you should check out the NCAP website for the Apprenticeship Program. The application period for the Apprenticeship Program has just opened and will close April 20th!

A Posting by Zefren Anderson, Emerging Artisan Hello! I’m Zefren Anderson from the 2017-2018 Navajo Cultural Arts Program (NCAP) cohort at Diné College. I’m a weaver and this year I am emphasizing not only in my own craft of weaving but also in sliversmithing. As part of our Materials and Resource class, Mark Deschinny of Church Rock came to Tsaile to teach us how to make weaving tools. With the prowess and mobility of an olden days Honaghaahnii trader, Mr. Deschinny is a weaving toolmaker to the People of the southwest (more at www.geocities.ws/deschinny/Looms_and_Supplies). Although we were off to a late start, I maintained an open mind – wondering if Mr. Deshchinny’s teachings would coincide with, be contrary to or be entirely new to my own. All teachings are valid to the clans that hold them, and it’s an interesting exchange of ideas when clans share teachings. I have been taught within the family traditions of the Hashtlishniis - if it works use it, if broke, fix it and if it can’t be used, repurpose and reuse. Many of our family tools are remnants of bigger whole tools. For example, old split battens finding new life as needles, sticks and finishing tools. I’ve found that many clans don’t do this, so I’ve not had much success making tools for weavers when they asked how they were made. The same goes for the many stories of the oral traditions of each clan along with the anthropological knowledge of the tool use, design and origin. In my own research of recreating pre 1868 Navajo Weavings, I’ve come to find the stories and museums were the best places to learn how to create the tools. They are different from the tools we use today, but they are they are both part of a long story of living and surviving. Mr. Deschinny arrived with tools and goals. Two big totes full of various woods, examples pieces, and a few power tools created a complete woodshop for our cohort. The goals were simple: Comb (Bee’adzoo’i), Batten (Bee’K’initl’ish) Spindle (Bee’adizi). We shared personal introductions and he let us in on the story of how he came to support his family from tool making. He also shared that his family’s history included the creation of a comprehensive dye chart for education. His family takes great care in tool making, using local sustainable wood, natural finishes, and a philosophy to avoid abuse of our natural resources like wood. Use of fire and darkening of the grain is prohibited. After some safety training, we set off to create our projects. Bee’adzoo’í can be made from gamble oak or in our case juniper. In the olden days, a whole branch is carved and sanded until it resembles a five fingered Bee’adzoo’í. But now we can use a saw to create multiple combs from one branch. Most modern Bee’adzoo’í are prized for evenness, aesthetic beauty and even the heaviness that creates tight hard weavings prized by collectors all over the world. I created my comb in the manner of my Shinaliadzaanbima. The comb manipulates the weft texture first then, it sets lightly into the warps. It is cut out exactly in the manner of one’s hand with their fingers outstretched set ¾” into the wood. The tips expose warp and keep weft tight. The area near the joints of the comb will stretch the weft and hide warp and a rounded pick at the opposite end of the comb. Why do we care so much about the weft? …. In the old story of the 1st weaving a problem arose on the weft spacing and warp due to tension irregularities created by changes in humidity. It allowed weaving resume outside a regular source of water and the weaver could adapt technique to the environment. Bee’K’initl’ish can be made from any hardwood. For our workshop we used Red oak. Steaming or wet earth bending can create the characteristic bend of a stable batten, Mr. Deshchinny uses weight as the wood cures. Tips are usually sanded up as the weavers prefer this shape. A state of mind and manual finesse coupled with a belt sander will produce great results for Bee’K’initl’ish. During this step, the NCAP Cohort members sanded and shaped their combs. Not surprising…their created tools showed the particular personalities of their creators. The finally sanding took the longest as we went from tool to tool, queuing on the saw and sanders while sharing stories and teachings. The Bee’K’initl’ish was created after all the tools required to warp up a weaving, is was found using for quick weaving in solid colors, passing long bundles of string between the wraps but when the humidity went down the batten would leave uneven spaces in the weaving as the air dried. Another tool needed to be made Bee’adizi can be made from anything culturally appropriate -clay, metal, wood or even concrete. In class, pieces were cut from a spilt juniper branch so everyone had enough time to complete one. Bee’adizi has changed over the last few years, as even more weavers are less dependent on Navajo Churro and Wool and more on brown sheep Company wool. Now weavers have one spindle where in the past there were several each suited to a particular task or fiber, even in the oral stories there are 5 spindles working yucca, cedar, cotton and wool. I wanted a general-purpose abalone spindle for a pre 1840s Biiheeh project. It needed to be light, fast, short and balanced manually. Using the curve of the spilt branch as a guide I shaped the whorl while Mr. Deshchinny leveled and drilled the hole. By the end of class I had a perfect spindle for my future projects and I’m grateful for this whole day experience. I’m sure most of the NCAP cohort members also enjoyed themselves and got more from workshop than what they expected. I’m looking forward to the next workshop -- Traditional Dye and spinning.

|

Categories

All

Archives

October 2021

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SocialsALL PHOTOS IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT PROTECTED. PHOTO IMAGES USE IS SUBJECT TO PERMISSION BY THE NAVAJO CULTURAL ARTS PROGRAM. NO FORM OF REPRODUCTION IS PERMITTED WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE NAVAJO CULTURAL ARTS PROGRAM. |

Featured Pages |