Dr. Christine Ami2020/21 American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Mentor

But I envisioned what the fellows could accomplish with such an opportunity so I put together a grant proposal based around three specific areas: (1) cultural knowledge of Navajo leadership and weaving; (2) economic knowledge of traditional Navajo female leadership and weaving sales; and (3) technical knowledge (practical experience) of implementing leadership skills and weaving techniques. Apart from those 3 goals, I wanted the fellows to gain insight into the practical maneuvering associated with my role as a grant manager, program manager, and instructor. This kind of knowledge could provide them with an example of how Native leaders (male and female) holistically approach their work and personal life. We often forget that how we care for our home and our immediate family is an excellent indicator and reflection of who we are as people. Too often, we, as a Native community, celebrate the work successes of our Navajo leaders but not much light is dedicated to how they ground themselves with family (or if they don’t). So this fellowship allowed for the fellows to observe how I balance (or don't balance) my responsibilities and obligations as a Navajo woman and as a college community member. And here is what we, Tamerra Martin, Valene Hatathli, Sue V. Begay, and I learned. The first lesson I learned from my fellows is that it is primordial to continually ground ourselves in our own powers as Navajo individuals, it's more important that establishing a public identity as a community leader. Tammy's interview with weaver Gloria Begay reinforced this teaching for me. Gloria's mother taught her that "You have ten fingers, those ten fingers are given to you so that you can take care of yourself; work with your hands”. That's right!, I thought reading that: Bilá’ ‘ashdla’ii nishłį́, Nihookaah Dine’é nishłį́, Diné nishłį́ - that is who I am - a 5 fingered, powerful, and blessed Navajo person - that is my affirmation to maintain self-motivation. And with both of my hands, the best work that I can do is lead myself with self-determination because it is what I have been built with. The next lesson that I learned was that our cultural arts has helped to inform the development of leadership abilities across generations. Valene interviewed Dr. Delores Greyeyes, the Director of Navajo Department of Corrections. Dr. Greyeyes was raised in a single parent household. Her mother was a weaver and used that skills to provide for her family. As Valene found out: "It is one's choice to act or to be idle. Everyone has a leadership journey; it begins with knowing yourself, the environment you are in, and finding solutions". That is how Dr. Greyeyes learned about T’áá hwo ajitéego , the practice of personal accountability. Another lesson in Navajo female leadership that the fellows brought forth was the need to make sure that we don't live for us, but for the future. Tammy worked with weaver, Marilyn Vigie Fausto, to expand her techniques in the twill weave. Tammy and Vigie had known each other for years before deciding to work as in a mentor/mentee relationship. I loved this set up because there is so much that we can learn from our peers - it's not just age that brings knowledge. But one of the strongest messages that was brought forth in this pairing was the ability to take what you have learned and teach someone else. Tammy recapped the terms of their agreement: "Marilyn agreed to teach me as long as I promised to teach others, even if it meant I teach my daughter". Planning for the future. There is a sense of humility - ádaahwiinítį́. Yes, I want to learn but it's not all about me anymore - It's not about me at all - It's for future generations. My fellows also taught me about self-assessing - siih hasin. And not the fluffy "let's self-reflect about all the good" - a kind of self-reflect about what needs to change. That self-reflection brings us back to re-evaluating our personal values and our immediate and long term goals. And here is where my fellows really taught me - As a leader: it's okay to not be able to do it all, it's okay to not be everywhere, it's okay to place family over work and weavings over publishings, and it's even okay to cut off negative relationships, to start new goals, and to admit when you are wrong. Sue V. Begay taught me that when she realized that she needed to work on family and weaving a bit more before she could commit full time to this fellowship. Direct, honest, and self-reflective communication based on self-assessment.  One of my shelves ... One of my shelves ... Mentee Growth: By the end of this fellowship, the fellows learned new weaving techniques with mentorships, practiced their conversation skills through interviews, learned about cultural arts businesses through business planning classes and workshop leading - all through the lenses of Navajo women leadership. Mentor Growth: I created new class syllabi for the emerging Native American Studies Minor program here at Diné College. One of which is NAS208: Native American Women. It's filled with topics from Indian Princesses to Women Warriors to Political Leaders to Matrilineal Obligations and Responsibilities. I was able to work on other topics that interested my fellows and created ; NAS301: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and NAS401: Indigenous Human/NonHuman Animal Relations classes. These classes address our relationships to the world around us, placing the environment and non-human animals as the protagonist in a world where we are not the center of attention but rather a link in an intricate web. I also completed an article manuscript based upon the memoir writing retreat entitled: "A Native Scholar Pushing Back: Epistemological Imperialism, Cultural Gaslighting, and Credential Theft." (forthcoming). That workshop really helped to build confidence in writing from my experiences. Community Growth: Together, our Indigenous Visionaries group built a little community - a community to celebrate, commiserate, and re-focus on leadership qualities we learned about over the past year: self-determination, personal accountability, humility and critical self-assessment informed by our community. We were blessed to work with brilliant Navajo leaders: Brenda Joshevama, Marilyn "Vigie" Fausto, Jessica Stago, Crystal Littleben, Gloria Begay, Delores Greyeyes, Velma Craig, and many, many more who helped us along this past year. Personal Growth: This fellowship provided me with a moment of clarity to reflect upon my own values, goals, and aspirations through the lens of ádaa'áhólyá - Navajo holistic self care. In order to do this - something had to go. So I checked back in with me:

At the end of this fellowship, I decided that the best course of action for my family and my goals was to step down as a grant and program manager. I am now allowing myself to transition back into the role of creator - weaver, potter, crocheter, baker, butcher - all the things I love that I can do with the 10 fingers provided to me by the holy people that make me feel whole. My main goal is to provide my sons with the leadership skills and tools necessary to be successful in this world as Bilá’ ‘ashdla’ii, as Nihookaah Dine’é, as Diné. And while my goals may change in the future, right now this is the best leader that I want to be right now. So thank you, Tammy, Valene, and Sue for showing me the path and for providing me with examples of Navajo women leaders.

0 Comments

Tamerra MartinNavajo Weaving BFA Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Fellow It is often said that people come into your life for a reason; it is up to you how you respond to their presence. As a parent to five children, certain teachers have left a big impact on our lives, from elementary to middle school to high school. And then there are people who come into our lives unexpectedly and we still learn a thing or two from them. My story is about how an aspiring weaver has taught me about twill weaving and then some.

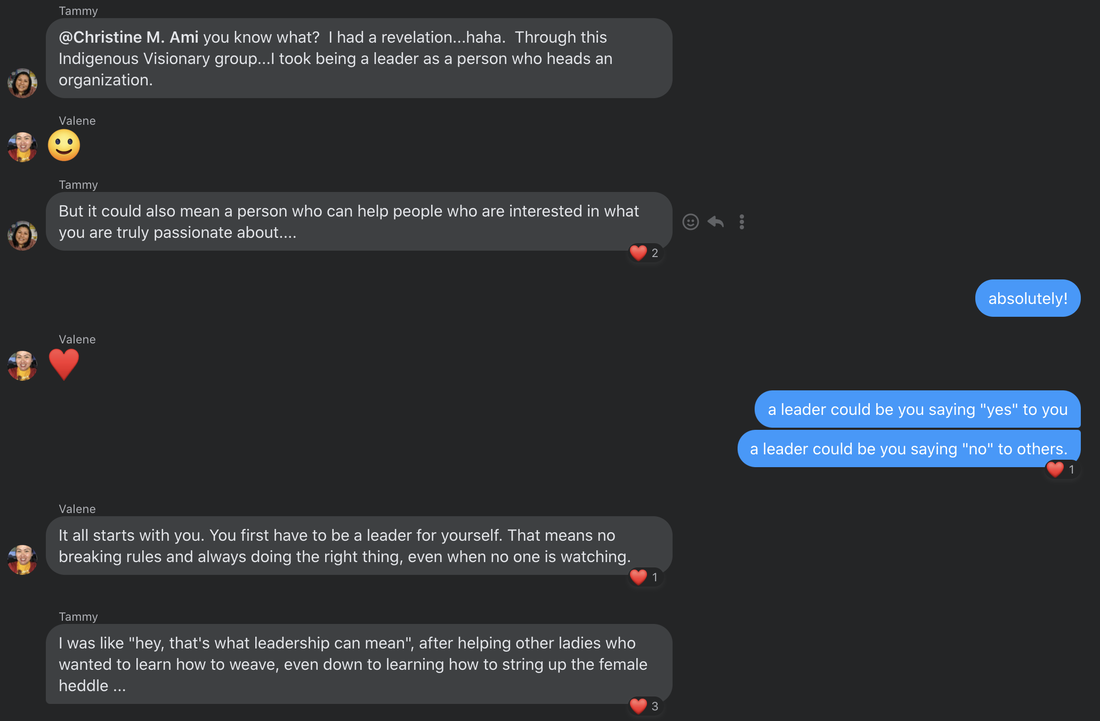

As she grew old enough to enter elementary school in the 1970’s, she was put into boarding school. The BIA run boarding schools were sometimes miles away from home, which meant little to no contact with family and home. For some children, continuing education meant going further and usually off the Navajo Nation thus called the Placement Program. In most cases, the quest to become educated meant that students lost a sense of their hogan (home) and their livelihood. Although she was gone from her family for so many years, she always wished to continue the gift of weaving. Her interest in learning to weave peaked as an adult; now living in the Valley of Arizona. The Heard Museum offered Weaving classes through financial grants that they would receive, these classes were conducted by world known textile artists, sisters, Barbara Teller Ornales and Lynda Teller Pete. One of these classes was held during the month of November of 2018. I had the privilege of attending this one week opportunity through the Navajo Cultural Arts Program via Diné College. It is here that we first met. I really enjoyed her enthusiasm for weaving and, basically, for everyday life which I still enjoy to this day. We kept in touch through social media, she’s always encouraged me in my endeavors, not just through weaving but through all the things that I am going through in life. Her and her husband have been encouraging to my daughter and her artistic endeavors as well. It was because of her genuineness that I chose Mrs. Fausto to be my mentor as part of the Indigenous Visionaries Fellowship. I especially wanted to learn more about her self-taught technique of Twill Weaving. I began to notice more and more that she was weaving twill and that she would mention how she was teaching others as well. I have woven a diamond twill before but had no idea how to incorporate other designs with the same heddle counts, and this is what she wanted me to learn. I have to admit that it was more frustrating than I thought it would be, sometimes the designs wouldn’t seem clear, or the count was off just by one or two--just close to giving up. It was through her encouragement and patience, for about three months, that I was able to finish my first small diamond twill sample that I was so proud of! She is still committed to teaching me the medium and large diamond twill weavings as well, so we are not done. This opportunity also brought up the spirit of a weaver. Half way through the mentoring experience, Marilyn informed me that she had been undergoing treatment/therapy for cancer. My response was to feel so emotionally torn; how could someone so gifted go through something like this? My promise to her meant all that much more; I have learned this twill so I could continue to teach her teachings. Regardless of this, she kept optimistic and strong--she encouraged me to maintain a positive attitude as I wove my twill sample. I also remembered that as you practice a traditional art/craft, you think and pray for the good things in life to those who are in your life. It was a July day when she sent a message that the results of a recent biopsy showed benign cells! It was such a blessing to read her message and give thanks to the Holy Beings for bringing such a great mentor into my life.

The biggest lesson I experienced from all of this was the weavers gift of receiving and sharing. Marilyn agreed to teach me as long as I promised to teach others, even if it meant I teach my daughter. Her wish was based on her own experience; she wanted to have someone teach her but in most instances she was given very broad instructions or she was asked to pay an outrageous amount. She didn’t want others to feel the way she did; so if I could learn these techniques from her, I would then share it with others who wish to learn; I plan to keep this promise as I perfect twill weaving. Recaping Indigenous Visionaries: The Burden and Blessing of Cultural Preservation as a Navajo Weaver10/12/2021 Valene HatathlieNavajo Cultural Arts Certificate Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Fellow

The feeling I have towards weaving is so intricate that takes me back to the precious times I had with my grandmother, Bessie Hatathlie. She was a master weaver who wove beautiful tapestries that she sold, traded, and donated to various people and institutions. Growing up I sat by my grandmother’s loom as she wove. I watched her card and spin wool for hours or until someone told me to do my chores. I was partially raised by my grandparents and I’ve spent a considerable amount of time with them. Their friends became my friends and sometimes they would all come to my grandma's house to dye wool in metal barrels over open fires that were spread all over the yard. I remember seeing the herbs in glass jars and the fires being built. Everyone brought their spun-undyed wool and they worked together to combine the herbs, water, and alum and began the process of dying wool. I was about 4 years old, too young to do much but watch. In my adulthood, I had a job that consumed much of my time. Many people my age lived in a constant cycle of work, go home, sleep, and go to work again. In my mid-thirties I wanted out because I wanted to explore life beyond the status quo. I wanted a challenge. Ironically, I found it by returning to my cultural roots and attending Diné College Navajo Cultural Arts Program while living in the city. As a student, I was introduced to many teachers like Tahnibaa Naataanii, Christine Ami, Sara Naataanii and Brenda Joshevama. All these women have taught me more about weaving, Diné culture and leadership then I could on my own. They have nurtured my leadership knowledge with their insight and reconnected me with my culture.

I also had the opportunity to run my own workshop on wool processing during the 2021 Navajo Cultural Arts Week! And I did it virtually so that anyone who could and wanted to check out the process could stop in and learn. I did that!

Valene A. Hatathlie Navajo Cultural Arts Certificate Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Fellow

Our conversation only reinforced the knowledge that Sa’ah Naagháí Bik’eh Hózhóón, which is a four-step process of Thinking, Planning, Implementation, and Reflection, is pivotal to a person’s success. Within this philosophy there is the practice of personal accountability – we call T’áá hwo ajitéego. And part of the self-accountability is learning how and when to help others. In the conversation Dr. Greyeyes, the second of nine children in her framily, revealed that a pivotal moment with her understanding of T’áá hwo ajitéego happened when she was about eight or nine years old after her mother, a woman raised her children based on traditional Navajo teachings and wove Navajo textiles to support her family, had made the well-thought-out decision to divorce her father to protect her children from domestic violence. As Dr. Greyeyes was out herding sheep, she watched them graze. Her focus shifted upward to the sky. In that silence, she made an oath to never let her own children go through the type of abuse her father inflicted on his family, and she swore to never leave her mother’s side. With mentors like her mother, Dr. Greyeyes and her family lived on top of Black Mesa. The struggle they experienced was a familiar one that resonates with other families on the Navajo Nation – that same lack of resources continues to plague us still. Dr. Greyeyes grew up knowing that people around her needed help. Knowing that there was missing infrastructure, she sought to build a judicial foundation on the Navajo Nation. To achieve that goal, she set out on a pathway of higher education. Early in her academic career, Dr. Greyeyes received an associated degree in human resources. She then went on to earn a bachelor’s and master’s in social work. She did not stop there. She continued onward and a received a Doctoral Degree in social justice with an emphasis in criminal justice. As she wrote her thesis, her research reminded her that cultural teaching is substantial in a person’s lifetime success Dr. Greyeyes believes these cultural teachings should be available to all Navajo people who want or need them. With the knowledge as her armor, she researches Native American prisoners and their journeys that have led them to the correctional system and their experiences while in the system. She learned they were eager for cultural teaching. She believes that early education roots individuals for lifetime achievements.

So the questions I have for myself now as I continue my leadership and weaving journeys:

(1) how will I be able to pull together my environmental concerns with my weaving knowledge and skills; (2) how can I use my voice to create change in those areas; (3) how will I choose to act? Dr. Christine AmiNCAP Grant Manager and 2020/21 American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Mentor March 31, 2021: I couldn't image a better last day of National Women's History Month than with a book discussion on I am Malala followed by a memoir writing workshop with none other than the president of the American Indian College Fund, Cheryl Crazy Bull!

Throughout our Virtual Connection, we had the opportunity to hear from several of the other Indigenous Visionaries fellows from: Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College and Salish Kootenai College. We touched upon some key points and personal connections with the text. I was particularly impacted by commentary from our own NCAP Visionary, Tammy Martin, who pointed out that she read the story of Malala, a young girl who was shot by the Taliban for advocating for eduction, through the eyes of young Nobel Peace Prize winner's parents. Our discussion moved from takes on feminism to the power of writing for women. One of our College Fund facilitators brought forth a quote from the reading that highlights the act of writing as activism. Malala writes:

I know, I know - I am getting a bit jargony here - but hang with me for a sec or two... Specifically, Spivak highlights: "Can the subalern speak? What must the elite do to watch out for the continuing construction of the subaltern? The question of 'woman' seems most problematics in this context" (90). Through her critical eye of Foucault and Deleuze, she concludes: "The subaltern cannot speak. There is no virtue in global laundry lists with 'woman' as a pious item. Representation has not withered away. The female intellectual as intellectual has a circumscribed task which she must not disown with a flourish" (104). So the question remains - how does the intellectual, even the female intellectual, represent these voices without being condescending, without commoditizing their knowledges and their experiences, without engaging with epistemic violence of academia? For Malala the answer is clear, don't wait for the academic - write for ourselves. Just as my mind started to wonder further into memories of literary theory and gender studies lectures, inquiries of what/who defines an "intellectual", and the complexities of my role as a Navajo woman with a Ph.D. in academia, our Indigenous Visionaries event flowed into a memoir writing workshop - I see what you did there, College Fund people... read a memoir, workshop our own memoirs ;)

You see, I write in stories - a highly controversial form of data delivery in the academic realm - second reader responses typically echo: where is the hypothesis?; is this the introduction?; why can't you just get to the point?; is this creative writing?, is it theory?, is this even research? My introductions are usually snapshots of when the perplexities of the study have culminated in a personal setting and my conclusions are usually finalized with my traditional introduction, reaffirmations of who I am as a Navajo woman. In between are hypotheses, data, theory and research. More importantly, these stories from my experiences, from my studies - both formal and informal - are how I learned to learn and how I learned to teach. From weaving to butchering, from graduate papers to my dissertation, from to my response to the Navajo Nation's president for silencing me to my current application for a National Endowment of the Humanities Grant - stories are where you will find my voice, my successes, my failures, my family - it is where you will find me. So vulnerability pretty much wraps up a lot of my anxieties about publishing. Cheryl pushed those vulnerability buttons and had us practice some writing - "How does your story start?" What better time to test out the starting line to my article draft, entitled: "A Native Scholar Pushing Back: Epistemological Imperialism, Academic Gaslighting, and Credential Theft". What would people say? What would my peers think? Despite the fact that the group I was writing with could not have been more supportive, vulnerability creeped in. Oh well... here I go: In the stillness of my home before the sun rose, before my children, husband and animals awoke, I was trying to make sense of the theft of my Indigenous research credentials by a non-Native former colleague. Heads nodding - That's a good zoom sign. A voice reached out: "I would read that!" Another voice followed, "Yeah, I would too." Followed by another, "Now, I want to know what happened!" Validation of my experience, of my voice, of not only others hearing me - but of others listening to me. It was only the first sentence and the story was still to come, but it was an opening line that epitomized a crucial moment in my life as an academic and a Native woman and which also interwove my experience in complex sociopolitical realities of the Native American Studies discipline. After our workshop, I thought about what was shared and what it means for a Native American Woman to write down her stories. My fingers reached for one of the first Native women's anthology that I had ever read, Reinventing the Enemy's Language (1997). Julia Coates, Councilor for the Cherokee Nation's Legislative Branch, and my first Native Women's Literature professor at UC Davis, introduced me to this compilation of poems, songs, and essays that bring to life the "beautiful survival" of Native women, including all of the ugly as Joy Harjo declares: "We are still here, still telling stories, still singing whether it be in our native language or in the 'enemy' tongue" (31). As my mind returned to the issues brought forth by Spivak, these questions returned: How can I write about Navajo women, from my position as an academic, and encapsulate their voice with mine? And then I thought - why do I have to encapsulate ALL Navajo women and why do I have to write like a western academic? What I write about is my experience as a Navajo woman and I write in stories.

These sensory textile narratives constitute creative acts of writing, complicate constructions of Indigenous feminisms, and promote cultural sovereignty through means other than the enemy’s language. And as I thought of those words and my place in academia, I thought of my grandmother. I thought of how she told me stories - it was through weaving. Weaving is our memoir - In the warp are stories of her survival and mine. Each line is a recap of my day, smooth hooks retell my successes, each section unwoven is not only the presentation of one of my failures but also my reattempt at troubleshooting the problem at hand. Inside my weavings are my thoughts - my family - my research - my vulnerabilities. Inside my weavings are told, unseen stories. I haven't woven a complete piece in years - work and life have kept my loom covered. I tried to look at my weaving tools that were my nálí's who passed away from COVID complications in July. But I just wasn't ready. But today - today is different. Today I picked up my spindle. The warp, my hand, my thigh became one instrument. My spit used to mat and settle the warping mixed with the wood of the spindle and in return that taste of wood brought forth the memory of the feel of my nálí's velveteen skirt - coated with a slight tinge of mutton grease. The sound of my spindle on the floor joined the sound of her spindle in my memory. Just like that - My grandmother, Cheryl, Gayatri, Julia, Joy, Inés, and I, we started a new piece - In this warp is the outline for my next memoir - this one includes the stories of the Visionary fellows and how they got their mentor to weave once more. It is filled with the vulnerabilities we discussed in our workshop, power that is associated with learning to write ones story, and continuation of our ways of knowing with a weaving comb in hand.

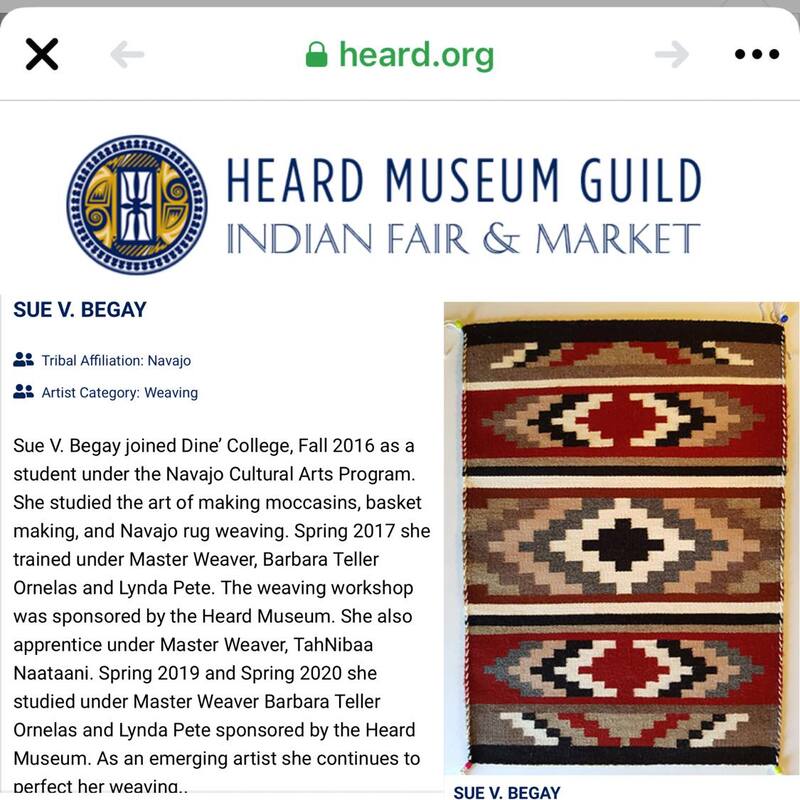

Sue V. BegayWeaving BFA Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Winter 2021 Fellow

Never once did I think that one day I would be amongst them as an artist. Well, it happened this year. With the encouragement from the Navajo Cultural Arts Program, my Visionaries' mentor, and one of my weaving mentors, Tahnibaa Nataanii, I completed the Heard Guild and Indian Market's application and submitted it. The application process was pretty simple – to be considered I submitted my art descriptions, pictures and paid an application fee. The hard part was waiting to hear if my art was accepted. The anticipation to receive word back as to whether or not I was accepted, waitlisted or rejected was almost too much...I didn't know if I would get it. It takes artists YEARs to get it.... but it came! I was accepted! Sue V. Begay from Dennehotso, Arizona got a spot at the Heard Museum! After I accepted and paid my booth fee, my thoughts were on how exciting and honored it was going to be placed among the super famous artists. Seriously though – Tahnibaa Nataanii, Lynda Pete, Barbara Teller Ornelas – they are my teachers, my friends and I was going to have our work shown next to theirs! I was happy to be amongst them even though it was a virtual experience.

I was elated to sell two of my three weaving pieces. The personal experience is self-achieving with lots of support and encouragement from your peers. If it were not for the support of Diné College programs I would not have had the opportunity to shine with the superstars.

I look forward to submitting again next year. I'll have to apply again and I am sure it will be an entirely unique experience to be selling there in person. A few pieces of advice that I have for my fellow emerging Navajo artists about entering into shows like the Heard Indian Market is:

The pictorial raised edge with an eagle design pillow shown below is one of my items that sold at The Heard. Tammy MartinNavajo Weaving BFA Student, American Indian College Fund Indigenous Visionaries Fellow

She was very happy with her sale because she got to keep the money. This money allowed her to buy graduation items she thought she wouldn’t be able to afford. She went on to attended Navajo Community College (now Diné College) and earned a certificate. She uprooted from her home area and moved to the Eastern Agency community of Crownpoint. It was here that she worked at Indian Health Services, the Navajo Nation Police Department, the Office of Vital Statistics, and Crownpoint Community School. She had married, had a family and a place to call home. Weaving became therapy because she soon found herself a victim to domestic violence. Two years after filing for divorce, her oldest daughter became ill with leukemia and passed away in April. During these trying times weaving de-stressed her and provided an extra income. Five years later, she married Kenneth Begay, a big supporter of Gloria and his stepchildren.

When teaching her students, she tells them to research other well known weavers and their textiles such as Roy Kady, sisters Barbara and Lynda Teller, Gilbert Nez-Begay, and Kevin Aspaas; they all have their own story for weaving, their styles are what makes them recognizable, even from a glance. She says “the more you learn about other weavers, the more you know about yourself and you can create your own style”. Learn your language, even if you know just a few words, you identify yourself as a Diné person; to learn that being Diné is unique. “No one can take that identity from you”. That is something that a lot of our youth are dealing with, they may feel embarrassed to speak it because they might get shamed for speaking; it should be that way, we should be encouraging all the youth to speak our language. The last is something that she recalls her mother sternly telling her “You have ten fingers, those ten fingers are given to you so that you can take care of yourself; work with your hands”. This was not just a saying, it is the Diné philosophy of self determination or T’aa Awoli Bee. I recall my own grandmother saying that whatever you want or desire is at the very tip of your fingers, it's up to you to make the rest of the hand, mind and body to work to earn it. Sometimes, we take for granted how much work you put into something has its own rewards, or sense of accomplishment. We ended the interview encouraging one another to keep weaving, carding, spinning, and learning. In Gloria’s words “Weaving is a non-stop learning process”. Download the full recap of Tammy's interview with Gloria here:

|

Categories

All

Archives

October 2021

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SocialsALL PHOTOS IMAGES ARE COPYRIGHT PROTECTED. PHOTO IMAGES USE IS SUBJECT TO PERMISSION BY THE NAVAJO CULTURAL ARTS PROGRAM. NO FORM OF REPRODUCTION IS PERMITTED WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE NAVAJO CULTURAL ARTS PROGRAM. |

Featured Pages |